Calchaquí Valle, Quebrada del Toro and Humahuaca

- Period: Late Intermediate

- Location: Argentina

- Burials: 255 individuals

- Archaeologists: Gheggi, MS

- Related Keyword/Categories: Trauma, Identity

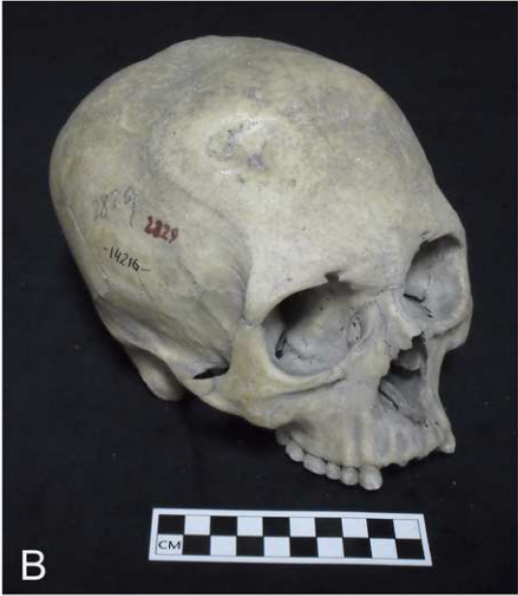

In Northwest Argentina during the Late Intermediate Period (900–1450 CE), it has been proposed that severe droughts led to reduction in food, collapse of exchange networks, and increased competition. This led to pervasive violence between communities, which in turn caused changes in social, economic and political processes including clustering of community groups for protection, intensification of agriculture, increased social inequality, and political fragmentation. This hypothesis is re-assessed by Gheggi (2014), who proposes using trauma patterns in human remains to determine what types of conflict, if any, were present and how this change occurred on a local scale. The sample for this study included crania (skulls) from nine sites found in NW Argentina within the Calchaquí Valle, Quebrada del Toro and Humahuaca. The complete sample included 255 crania, but only 223 were at least 75% complete and therefore well-preserved enough for study. All bones were taken from museum collections, which have limited information on the exact site or tomb they were taken from, though all have information on region and date. Broad localities allowed for some spatial comparison between trauma patterns. All individuals were assigned sex and broad age groups in order to better interpret the trauma patterns. In total there were 92 male adults, 111 female adults, 2 unknown adults, and 18 sub-adults. Trauma was recorded by the location and presence on which bone, the state of healing, shape and number of injuries, and size and location were precisely recorded. The analysis of trauma revealed that 39 individuals showed signs of injury including 15 female adults, 22 male adults, and 2 indeterminate adults. No sub-adults had evidence of cranial trauma. 39 of these individuals had only one lesion, and the rest had two or three. 37 individuals had pre-mortem trauma, meaning the injury occurred before death and showed some signs of healing. 2 had evidence for perimortem trauma, meaning it occurred at the time of death. Most injuries were found at the front or back of the skull, though the spread wasn’t statistically significant. Based on these results, Gheggi (2014) concludes that there was no specific group targeted for violence; both men and women suffered from it. The high proportion of healed injuries also suggests that the goal may have been wounding and disarming, not killing these individuals. This corresponds with other studies that argue violence was not large scale warfare or conquest of territories. Instead, conflict consisted of small raiding parties, ambushes, and taking of prisoners, food or goods. Further, in general the skulls show signs of overall good health and lack of stress markers. Usually, in populations face with all out warfare over long periods there are signs of stress due to loss of individuals to work agricultural fields, movement of food to armies, and loss of homes or exchange networks. Therefore, the changes we see during this period were not due to war, but rather low-level conflict.

References: Gheggi, MS (2014). Conflict in Pre-Hispanic Northwest Argentina : Implications Arising From Human Bone Trauma Patterns International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. DOI: 10.1002/oa.2391